The Stakes of Identity

Over the last few weeks one particular article has generated a bit of buzz online. It is Caleb Morell’s piece, Stop Finding Your Identity in Christ. And with a title like that, well you’d expect buzz, right?

I found both the article itself and the discussion it generated intriguing and enlightening. This was in no small part the case because it interacted with a bunch of things that had been slowly percolating in my brain for some time. However, before I share some of my reflections on the article, regular readers of mine will be able to guess what is coming next. Go on. You know that you really should read it first yourself. Look, you don’t even need to go back up to the previous paragraph to click on it. I’ll put another link to it right here. See you back here soon.

Identifying Identity

Early on in his piece, Morell identifies just how deeply embedded the language of identity has become within the contemporary Christian discourse. He particularly notes how pervasive the phrase “identity in Christ” has become.

The category of “identity in Christ” is so ubiquitous that it appears as the catch-all antidote to every Christian struggle. Do you struggle with sexual sin? Identity in Christ is the solution. Are you looking for satisfaction in a spouse? “Find your identity in Christ,” someone will tell you. Are you overly focused on people-pleasing? Your identity in Christ is the solution.

Morell is right. The phrase is ubiquitous. It’s everywhere. But just as interesting as how frequently we use it is how seamlessly we’ve integrated it into our theological and pastoral zeitgeist.

Here again, Morell is correct. To “find your identity in Christ” basically reflects how we think of the ‘end-game’ of the individual Christian life. The world tempts me to find my value, my dignity, my significance, my belonging based on any range of other factors about myself and my context in this world. Some of those factors are honourable and to be celebrated. Others are not. But either way, as we tell ourselves and each other, those things shouldn’t determine our ultimate identity. And if they do, well that means we’ve made an idol out of them. Instead we need to find—or locate—our identity in Christ.

Now in one sense… yeah, so what? I mean, surely we should be looking to find our authentic sense of personhood in Christ! After all, Christ is the most authentic person to have ever personed on this earth!

But to answer that question we first need to recognise that there’s a problem with this theological commitment and and how it intersects with contemporary notions of identity.

Identifying Identity’s Newness

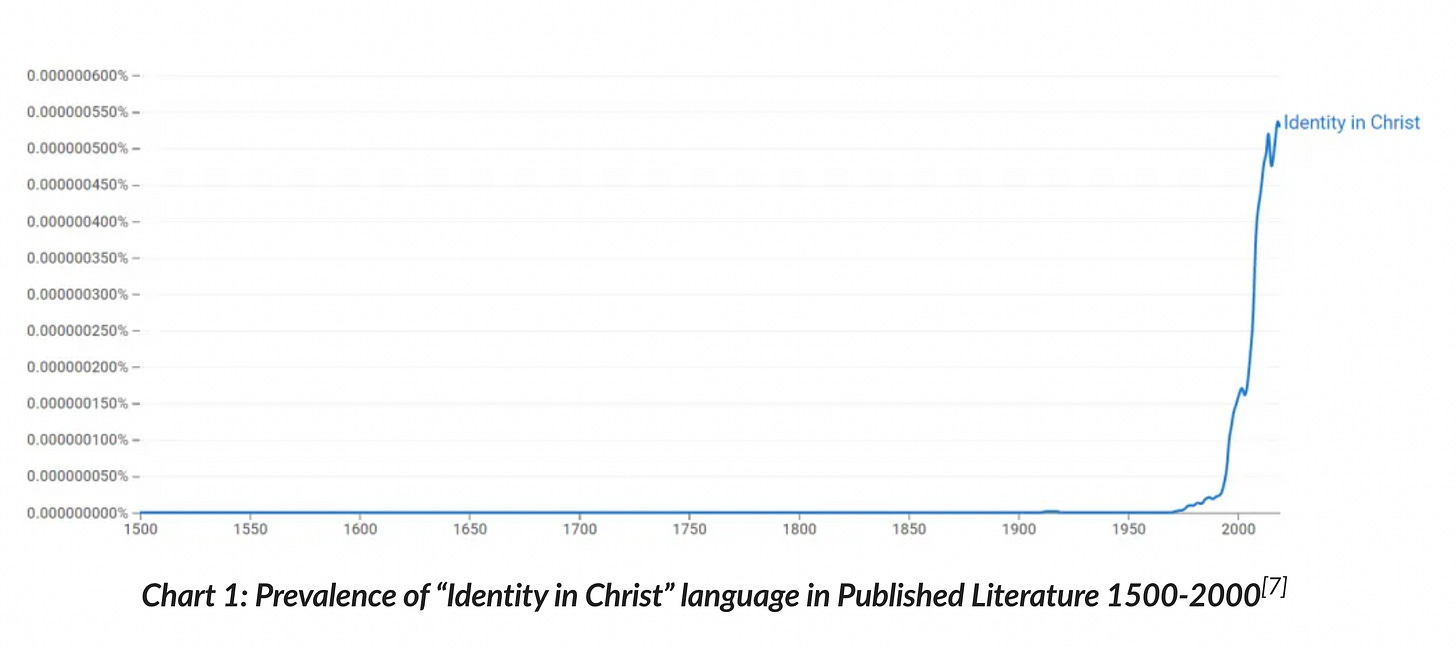

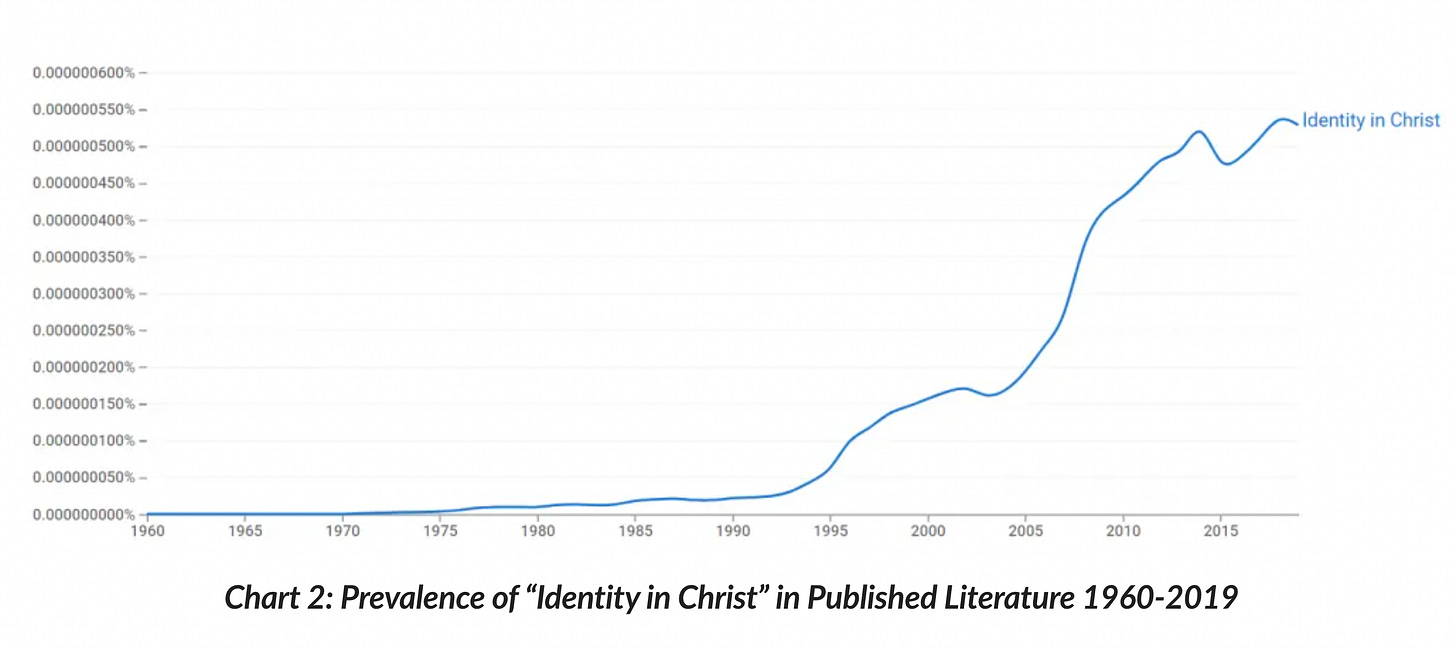

There was one particular aspect of Morell’s article which had me geeking out a little. It’s where he presents data (in handy graph form) of the historical and contemporary usage of identity language (in published literature), and especially of the phrase ‘identity in Christ’.

The screenshots below are taken from the article (Copyright © 2021 American Reformer). Now, when you look at them don’t get bogged down in the numbers and the details. Instead, read each chart’s title and then observe their general trajectory… their “vibe” if you will.

Images Copyright © 2021 American Reformer: ‘Stop Finding Your Identity in Christ’

You can see the pattern, right? It’s both pretty interesting and pretty important. Morell explains:

Searching the words “identity in Christ” in every published work since the Reformation immediately reveals that such language is almost exclusively a phenomenon of the late 20th century.

Now, some of Morell’s critics have been quick to say that just because something is new doesn’t make it wrong. Perhaps Morell is just a bit of a stick in the mud who doesn’t like change but needs to get with the times?

I agree that just because a phrase has entered our discourse relatively recently doesn’t mean we should just regard it as unhelpful, irrelevant, suspicious or wrong. If nothing else, the dramatically sharp incline in those graphs indicate that the phrase “identity in Christ” has today come to mean something important, to express something important, to be a response to something important. So no, we shouldn’t just chuck out the notion because it’s new.

But the thing is, that’s not Morell’s point. He’s not saying:

New = Necessarily Suspicious ∴ Return To Ye Olde Worldy Phrases.

Rather, his argument is that the phrase’s:

Newness + Ubiquity = Something Ideological Is Going On ∴ We Need To Be Aware Of What That Is

Identifying Identity’s Ideology

What ideological thing is going on? Well, I’m not going to rehearse Morell’s argument in any great detail because you can go and read it yourself. (And if you do then you’ll see the critique of him as a linguistic fuddy-duddy who simply doesn’t like new-fangled stuff is unfair). So instead, highlights:

Identity is not a neutral term in our day and age. Nor does it just mean “things to know about me”. Rather, the language of identity speaks to an ideological commitment that I have a true, authentic, somewhat hidden self buried inside me and the grand adventure and responsibility of my life is to discover that authentic self and make it known. In other words, identity today is not so much about how I might be known in context, but rather how I might be found by myself.

We Christians seek to head off some of the troubling aspects of that ideology by urging people to see the only thing that will bring ultimate fulfilment in life is not found in anything of ourselves, but in Christ alone.

But here’s the thing. By seeking to speak to the culture (i.e., identity seekers) through adopting the language of that culture (i.e., identity) there is a very real danger that we have unwittingly bought into the world’s ideology of identity (i.e., identity is what we make of ourselves).

Morell writes:

If you start paying attention, you will notice that the Christian use of “identity” is almost always preceded by the verb finding. Many, if not most, baptismal testimonies I have heard in recent years involve some form of, “I used to find my identity in [x], now I find my identity in Christ.”

Think about the language for just a moment: ”Now I find my identity in Christ”.

In the context of a world obsessed with identity as self-expression and self-fulfilment, what that phrase communicates is: “Jesus is what makes me the most me I could ever be”.

You know what it makes me think of? Tom Cruise. Or more aptly, one of Tom Cruise’s most quotable movie quotes. “I find my identity in Christ” is basically the equivalent of saying to Jesus:

Or if we’re going to be a little more cynical about it:

(Comic aside: For a great follow-thru on this analogy, check out this tweet from Glen Scrivener)

In the context of the way the world understands identity, the phrase “I find my identity in Christ” turns Jesus into the missing puzzle piece that makes me whole, that makes me complete, that makes me who (deep down) I always knew I was meant to be.

Identifying (Christian) Identity’s “Foundness”

So, what are we to do then?

Well, Paul linked his sense of “foundness” with his relationship to Christ in his letter to the Philippians:

Indeed, I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things and count them as rubbish, in order that I may gain Christand be found in him,not having a righteousness of my own that comes from the law, but that which comes through faith in Christ, the righteousness from God that depends on faith—that I may know him and the power of his resurrection, and may share his sufferings, becoming like him in his death,that by any means possible I may attain the resurrection from the dead. - Philippians 3:8-10

Ah ha! So we should find ourselves in Christ after all!? Weeeeell… go back and read the phrase again, in its context. Because when you do what you’ll notice is that the verb isn’t active. It is passive.

That is, Paul isn’t the one doing any finding. Instead, he is found. Paul isn’t finding himself in Christ. Rather, he is found—by God—in him.

Modern identity ideology’s hope is grounded in finding ourselves, so that we may truly know ourselves, in order to make ourselves right with ourselves through self-actualisation.

Paul’s hope was grounded in knowing Christ, so that he might be truly found in Christ, in order that, by faith, he might be made right with God through Christ’s righteousness.

“Now, I find my identity in Christ” certainly says something.

But it doesn’t say that.